An Azerbaijani’s journey exploring Iceland’s singing competition culture, and nature.

Author: Tural Abdulla

Have you ever watched a music competition, voted for your favourite song, only to get upset when the song you voted for didn’t win! Depending on how invested you were in the contest, you might have just shrugged it off, thinking ‘better luck next time, or screamed bloody murder at the television, complaining about how corrupt and unfair these kinds of competitions are, that the producers will do everything to control the outcome, or someone cheated, etc.?

But what is fairness, and to whom does it apply? To you? To the artists? To the contest itself?

To help me find answers to those questions I headed to Iceland, the Land of Fire and Ice, with the help and support from ActinArt, and I am very grateful for this opportunity given to me!

And who am I, you might ask? Well, I am a huge Eurovision fan, and I have the privilege to have Eurovision as a focus for my master’s studies in Cultural Management at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theater in Tallinn. I am originally from Baku in Azerbaijan, the Land of Fire, but I have been living in Estonia for close to a decade now. I’m also the vice-president of the official Azerbaijani Eurovision fan-club OGAE Azerbaijan, for which I also do interviews with artists. If interested, check out our YouTube channel.

Eurovision

For those of you that are unfamiliar with The Eurovision Song Contest, it is an annual international singing contest organized by EBU – The European Broadcasting Union. More than 40 different countries participate, each represented by a song, the artist(s) performing it, and the national broadcaster from that country that is a member of the EBU. Each year, upwards of 200 million people watch the contest unfold on the small screen in May, to see who wins this year’s trophy – or simply to see what crazy things will be on stage this year; are we going to have a burning piano on stage, a dancer in a hamster wheel, milkmaids churning butter… you never know with Eurovision!

To find out which artist gets to represent a country, the national broadcaster will hold local contests to figure this out. In some countries, this is entirely an internal process, where a panel of judges will evaluate potential candidates and simply announce who the representative is. But in many countries, this is a public selection, sometimes with multiple rounds of television shows to find the final winner and representative. And this is where my journey to Iceland starts, with the Icelandic local selection show called Söngvakeppnin, which is produced by the Icelandic broadcaster RÚV.

Söngvakeppnin

Söngvakeppnin (which simply translates to song contest) has been around since 1981, but Iceland, as the last of the Nordic countries, didn’t join Eurovision until 1986. Söngvakeppnin is now one of the main tv events of the year in Iceland. This year, in 2022, the reach of the finale was 63.7%.

My trip to Iceland gave me the opportunity to talk to all the finalists in this year’s Söngvakeppnin (Katla, Amarosis, Reykjavíkurdætur, Stefán Óli, and Systur (Sigga, Beta and Elín)), as well as with Felix Bergsson, the Icelandic Head of Delegation for the Eurovision Song Contest and a member of the Eurovision Reference Group. This gave me the opportunity to interview them about how they perceive fairness in Söngvakeppnin, how they feel they are being treated by the broadcaster and producers of the show, to get input on the topic of fairness on a smaller scale than that of Eurovision, but still a scale of large TV production.

Fairness

But how do we define what is fair? Does that mean that everyone is treated exactly the same way? Does it mean that no one gets more attention than others? In a music competition show like this, is it even possible?

Walking around Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland, where about two-thirds of the Icelandic population lives, there were advertisements for Söngvakeppnin and for the finalists on bus stops and similar advertisement monitors around town. One thing I noticed, in particular, was that all the finalists got the same amount of advertisement time. Everyone was showcased with the number of people needed to call in order to vote for them in the final show. So in that regard, it seems that everyone was treated equally!

Interviewing the artists, they were all appreciative of RÚV, and its commitment to them. They all thought they got fair treatment in the contest and didn’t feel like there was any form of favouritism from the producers. The artists had various degrees of experience, from Stefán Óli for whom Söngvakeppnin was the first time standing on stage in front of a live audience, to Reykjavíkurdætur, an all-female band that has performed internationally. Overall, the artists expressed that they thought the help and support they got from RÚV and the producers were fair and equally supportive.

The one thing a few mentioned as slightly unfair was the voting procedure. That anyone could vote as many times as they wanted, thus you could in essence buy the victory if you had enough money to send enough votes. To put this into perspective, in the super-final a total of 58626 votes were cast, with 35156 of those votes going to the winners Systur – approximately 12000 more votes than the runner-up. Let’s break it down a bit. The cost to vote was approximately 1.10 euros, meaning the total costs for the super-final votes were around 65000 euros. So if you had that kind of money lying around and if you could get to the super-final, meaning getting through the semi-final and initial final, which both included professional juries casting votes as well, the victory could be ensured. Those are some rather big ifs though.

With Felix Bergsson, the Icelandic Head of Delegation, the talks turned more towards Eurovision, and while he did acknowledge the existence of some voting irregularities in the form of bloc voting and diaspora voting, he didn’t think they were significant enough to have an overall negative impact of the fairness of the voting system in Eurovision.

Bloc voting is the phenomenon that some countries, in particular geographically or culturally close countries, tend to vote for each other. A clear example of this is Greece and Cyprus, which in Eurovision always give each other top points. Always. Another example is the Nordic countries, like Iceland, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, which usually always vote for each other. Diaspora voting is similar, but where bloc voting is mutual voting, diaspora voting is one-way. This is generally caused by a large group of people from one country living in another. An example of this is Lithuanians living in Norway. In the past two decades, the number of Lithuanians living in Norway has increased significantly, and so have the points granted by the Norwegian viewers to Lithuania. Every year in the past decade, Lithuania has been among the top three countries in the Norwegian votes, even in years where no one else voted for Lithuania!

With regards to Söngvakeppnin, Felix did mention that, at some point, the broadcaster was going as far as making sure every single entry got an equal amount of playtime on the public radio stations in order to make sure no kind of favouritism was in play by RÚV – who is also the broadcaster behind those radio stations. He said though, that in this day and age, with music streaming services, YouTube, and of course other private radio stations not subject to this, those restrictions didn’t have much meaning anymore, and the hard rule that every song needs the same amount of airtime has been lessened.

Personally, from what I experienced in Iceland and the short behind-the-scenes glimpse I had into the world of Söngvakeppnin, it did feel that the producers tried their best to provide an equal and fair platform for the artists to compete on. Sure, the stage show was vastly different from act to act, with Reykjavíkurdætur being the most elaborate one. But one has to keep in mind that at the end of the day, it is an entertainment show, and what fits for a high tempo song like Turn This Around doesn’t necessarily fit for a slower folksy song like Með Hækkandi Sól. The fact that a person can vote an unlimited number of times could add some unfairness to the voting part, though I doubt this fact had any significant effect on the outcome. I do disagree with Felix though. I think bloc and diaspora voting has an impact on the fairness of the vote in Eurovision, which impacts the overall result of the competition. The contest has a rule that you cannot vote for your own country but living abroad kind of circumvents that. The technology exists today to verify a person’s nationality, but if the EBU is willing to commit to this, and people are willing to go through the process of getting verified just to vote in a contest, is a completely different topic!

Iceland

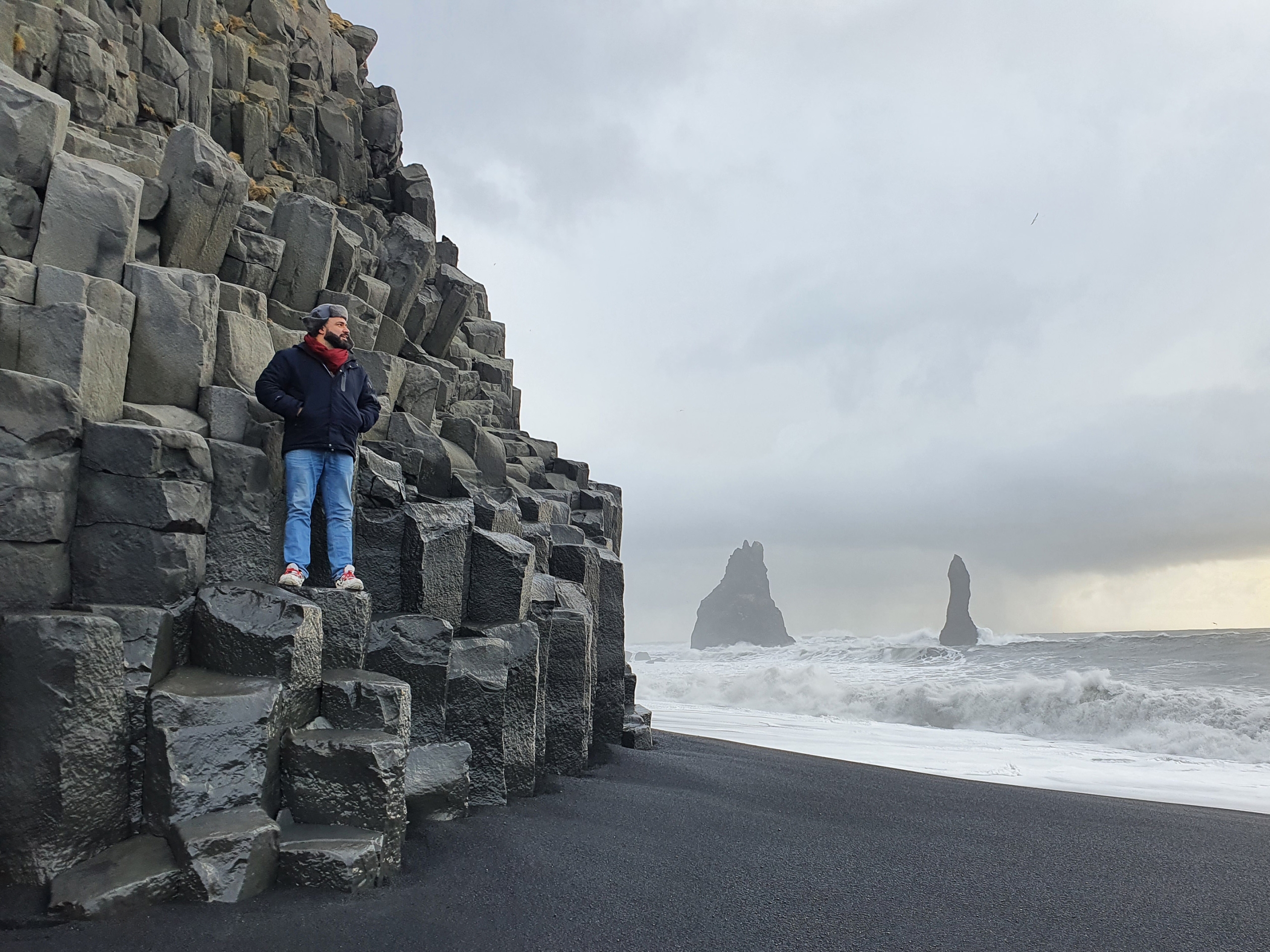

My trip to Iceland also included a few days where I had time to explore parts of the island and its breathtaking and inspiring nature, as well as the history of Iceland and its sagas. But, while I was in awe of all the nature and sights Iceland has to offer, my wallet was screaming at me – Iceland is not exactly a cheap country to visit! But even though I visited Iceland in the middle of March, thus in wintertime, it was still beautiful everywhere you looked. I got to experience things I’ve never seen before in my life. A geyser erupts, sending water twenty meters up in the air. Walking up to and touching glaciers in their out-of-this-world blue colours. Got to see the black sand beach and the crashing waves coming in that can easily drag a person with it out into the ocean if not careful – which also carries the very politically incorrect nickname “Chinese Takeaway” among some of the locals. Got to bathe in the thermic baths and smell the sulfur from some of the raw sources – this smell I could probably have done without! Bathing in these thermic pools while the air temperature is freezing is quite an experience. Your body is submerged in 40 degrees warm water, but the air temperature is minus five degrees. And on the very last night, before my flight home, I got to experience a fantastic display of northern lights in the sky! Sure, a cynic would probably complain that this particular display was mostly in the white and greenish colours, but I was still standing in awe with my mouth open, watching the lines swirl and dance across the sky!

Final words

I came to Iceland with the purpose of looking at the unfairness in competitions. What I found was, that for the most part it was handled fairly, at least in the Icelandic selection show. Both are seen from the participant’s point of view, as well as from the producers’ point of view.

I also came to Iceland to tick off a country from my bucket list. Iceland had for a long time been on my list of countries to visit, and oh boy, did Iceland deliver! I may have left Iceland financially significantly poorer than when I arrived, but with me home I took an experience of a lifetime!