Author: Virgo Sillamaa, March 2022

In the spring of 2021, I conducted two workshops for ActinArt on goal setting and career development for young musicians emerging from the somewhat closed and protected world of the music academy. The topic is close to my heart as when I myself was trying to figure out how to build a career as a young freelance musician in the early 2000s mainly working in the improvised music scene, I was continually perplexed by how to make the “right” choices, and prioritise my time and efforts. I, like many other musicians, was unsure to what degree I should try to forge my success or whether it was just supposed to happen. The classic talent vs hard work conundrum. With moderate wisdom of hindsight, I now know that I lacked a clear(er) understanding of what success means to me. Also, my music education didn’t really include any insight into how the professional music world works. Beyond the informal chats with my teachers – and I really had some great teachers and mentors – the curriculum was filled with a lot of how to make music, but very little of how to make a life out of making music.

Much has changed since then, of course, but the challenges remain and many young professionals emerging from the protected academic gardens of music struggle to find their feet. What follows is a brief account of how I approached these themes in my workshops “Between Zero and One” and some afterthoughts on my own learnings.

Part I. The concepts

Career – the noun and the verb

When seeking to understand a concept I often turn first to the dictionary – especially when thinking and writing in English which is not my native tongue. I do this even – and perhaps especially – with words that are ordinary, just to challenge my current knowledge. When checking out the word “career”, I was surprised to find that in addition to the noun, which we are all very familiar with, it is also a verb. I wouldn’t otherwise make news out of the fact that I still keep learning English, but the word “career” brings together a pair of meanings that capture the challenge of developing a career simply so well – just see below.

As the word’s double meaning seems to suggest, the challenge of developing a career – that is, a stable professional path with reasonable opportunities for progress – is how to manage this when real life all around us keeps careering largely beyond our control?

No doubt, there have been and still are areas of work where a career as a concept is very much alive and well. Think of public service, especially in countries such as France or Germany, but also in the European Union institutions. One starts young and given enough talent and perseverance, moves up the proverbial “ladder”. However, in the field of culture and creative industries, where the share of freelancers is higher than in any other sector and the structure of much work is project-based, how useful is the concept of a “career” for describing the relationship a young professional is to have with society?

The worthless plans and the value of planning

In my numerous discussions with various musicians on careers and the merits of trying to plan for one, many – if not most – are sceptical. Their own professional paths have been full of unexpected twists and turns, haphazard choices and risk-taking, and a lot of serendipity. How could I ever have planned for this particular event that turned out to be a career-maker? That’s a thought I’ve heard a lot. And the logic is convincing – it’s too uncertain, too random, all you can do is seize an opportunity coming your way (and of course practice like mad when you’re young). Yet, when looking back on a fulfilling career then it doesn’t look like a pattern of random events where the protagonist is simply a victim of blind luck or the lack of it. We read too much into the events that open doors and recognise too little the values, attitudes, skills, experience and cultivated confidence it takes to walk through them and be able to make something lasting out of the opportunities we’ve half-crashed into.

There is a famous saying, often probably falsely attributed to Eisenhower or Churchill, that “plans are worthless, but planning is everything”. I live by that daily myself, doing a lot of planning, while not really having definite plans for almost anything. I believe plans and planning are too often considered as essentially the same thing. That since “no plan has ever survived contact with reality”, as another famous saying goes, planning is a form of self-delusion, at least when it comes to such careering phenomena as careers in music. But there is a difference. A plan is a fixed thing, increasingly out of date by definition. Planning is an active open-ended mental activity that pushes us to understand both ourselves and our environment, to figure out creative ways to align them and take action. Plans can and must change as the reality around us is changing in uncertain ways. Of course, in music as in all creative fields, well developed artistic talent is still the most important thing. But the person embodying it can make bad decisions, get caught into harmful contracts or unfair partnerships, burn out and become lost, perhaps before reaching their full potential. It takes a lot of skill to play the violin really well. But so does living the life of a violinist.

Great, let’s then learn and teach planning, creative and strategic thinking and cultivate open and courageous i.e entrepreneurial mindsets. But how? There are decades of learning sciences research and practice out there which I’m unfortunately mostly unaware of and cannot bring to bear on the situation, so I tried to tackle this through looking into my own life experience and drawing out a few useful frames of thinking.

Part II. The workshop

Between zero and one

I called the workshop “Between Zero and One” which is snatched from inspired by a book by the infamous and controversial venture capitalist Peter Thiel. His book “From Zero to One” is based on a series of lectures he gave on how to build startups. Drawing from his own illustrious career, he states that “every time we create something new we go from zero to one” and it’s the hardest, riskiest phase, requiring an “entrepreneurial spirit” and vision to pull through. Going from one to the multitude is a mere administrative affair compared to the inception of something new. I’ve always felt it’s an apt metaphor also for freelancing professionals operating in the cultural sphere. The money in the form of investment – or support as is often the case in cultural projects – being spun into these endeavours is orders of magnitude different, but the mental models needed to deal with high levels of risk and uncertainty are comparable.

The key elements in the workshop were:

(i) Clearing the meanings behind concepts such as “career” and “planning”, which I covered in the first paragraphs of this piece

(ii) Identifying the two crucial objects of our inquiry – ourselves and our environment – and looking into both

(iii) Creating a framework for thinking on multiple levels about our professional life and activities.

I also tried to be interactive. The participants had to fill a very brief survey before the half-day session, answering questions about what are their big goals and the big challenges to reach them, etc. In the middle of the session, we did interactive group work, which in spite of my best intentions was probably the weakest element in my offer. Finally, we also had some Q&A in the end. All of these elements taught me a lot and I will summarise the learnings in the final part of this essay.

Know thyself and also thine environment

After coming to terms, literally, with the notion that we can try to steer our career with strategic thinking and planning, the next logical questions are: steer towards what and through which kind of an environment? I proposed to think of these two independently, as the inner and outer reality. The goals we set must relate to ourselves, our intentions giving us directions and milestones. The environment, in this case, is the music sector which I liken to an ecosystem as it’s complex, dynamic, and thus impossible to fully predict, even in theory.

The inner reality – yourself – is about answering questions like:

- What kind of a life do you want to lead as a creative artist? How do you define success?

- What is the risk level you are willing to endure in order to pursue creative freedom?

- What matters to you and what makes you happy? Or, put in another way, what doesn’t drive you crazy?

It’s important to think about one’s level of ambition and the price you have to pay to achieve and maintain a very high level of (perceived) success. While teaching about the music business to young musicians wishing to become successful artists, I’ve noticed they are often somewhat discouraged to find that success – that for many is fame and visibility, a high status among peers and recognition in society at large – is not a comfortable plateau to be reached and then enjoyed, but a constant state of high intensity searching and delivering. Only some people find it enjoyable enough to consider the tradeoff worthwhile.

Also, being a freelancer, irrespective of the level of success, requires a moderate-to-high tolerance of risk and uncertainty. As it takes a long time to develop even a moderate career, one must at least to a degree enjoy the freedoms more than the stress brought on by constant uncertainties. Finally, a freelancer must be able to self-manage on all levels: from long-term goal setting to everyday task management, from keeping high professional standards – and I don’t only mean sight-reading skills, but also answering emails effectively and on time – when working with others and, last but not least, have the entrepreneurial initiative to launch and lead one’s own projects. The phrase “entrepreneurial mindset” is possibly diluted by overuse, but for me, entrepreneurialism has a very clear and useful meaning. I take it in the Schumpeterian sense of an ability to lead change and navigate the creative destruction that new ideas inevitably cause. All freelancers have to be entrepreneurial enough to take care of their business, both literally and metaphorically.

The trouble with learning about yourself is that it can only be done through real experiences. “Find your passion” is an easy piece of advice to give, but very hard to take. All that I wrote above – know your life goals, level of ambition, risk tolerance, and be entrepreneurial – are empty words until given concrete meaning through personal experience. The old adage is true: you can only learn by doing and it will take time. This is not an easy lesson to give. Instead of getting a set of instructions in the beginning and then going out in the world to fulfil a career plan, one needs to figure out personal preferences through some years of trial and error. This sounds more like a recipe for careering than for a career.

In a successful instruction book, the above reasoning would at this point be followed up by some brilliant advice on how to hack this problem, make the right three choices, take the best seven steps and get ahead while young. Well, I don’t think there’s a hack for gaining experience other than taking the time and accepting the risks. That’s why these topics cannot be delegated to a half-day or even a half-year separate course on “how to develop your career”, but must run like a thread through all education and beyond.

The outer reality – the music ecosystem – can be learned about through asking questions like:

- How does the music sector work? Who does what and why?

- Who are the key people for me and how can I reach them?

- How can music be made into a professional career with an income able to sustain my creative activities?

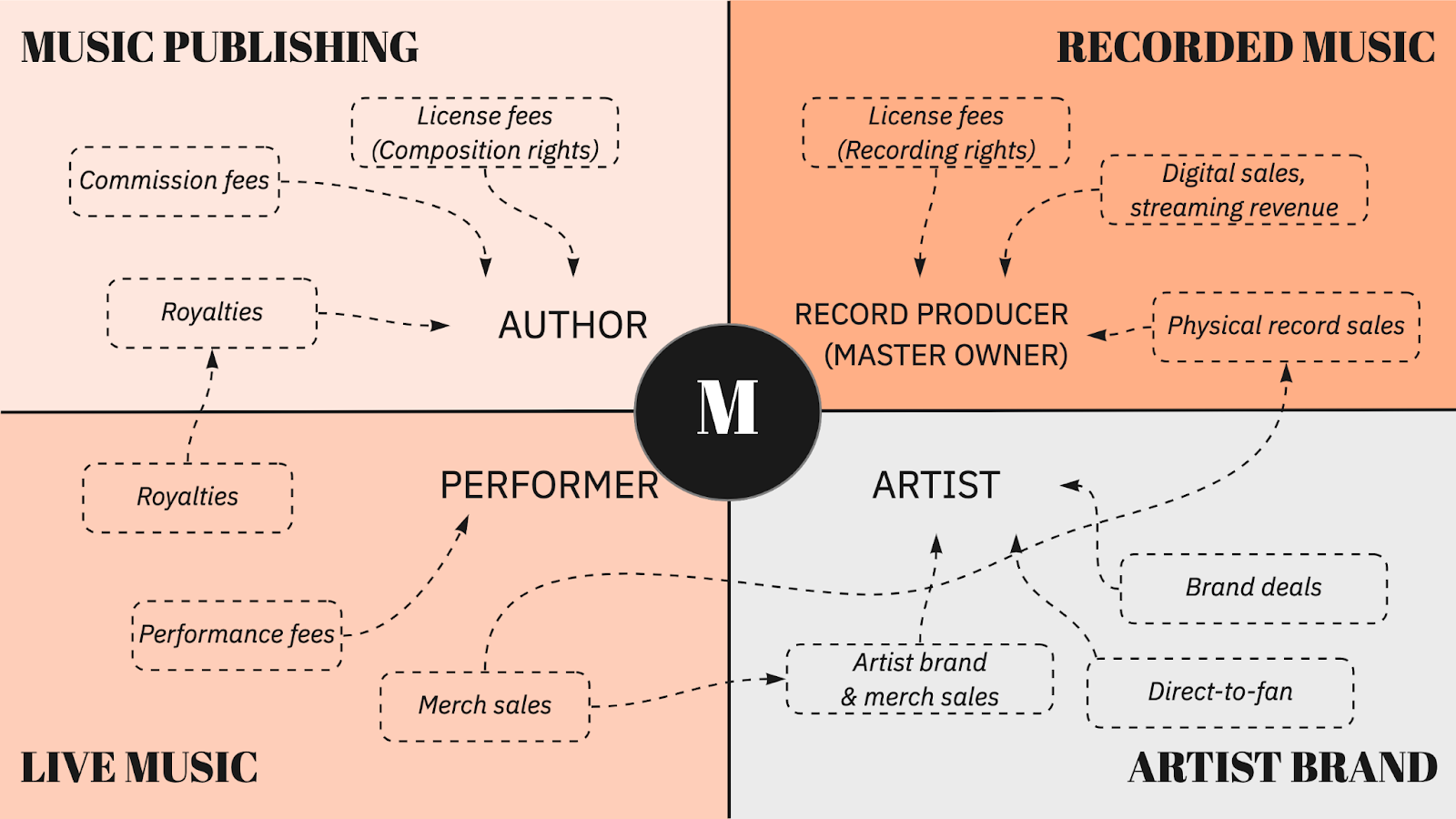

In the workshop, I presented a version of how to understand the music business. There is no reason to redraw it all here, but at the minimum, all music students should get an explanation of the various ways music makes money and provides income, who are the different players in the scene and what do they actually do – from agents, presenters, A&R’s to artist managers, music publishers and radio & playlist pluggers. See figures 1 and 2 as examples of how I explained these things in the workshop.

Figure 1. Economic value creation in the music ecosystem

Figure 2. Key roles and relationships in music publishing

I’ve heard many times the argument that all this is not necessary for classical music students as they simply need to perform at an absolute peak level and all the rest resolves itself along the way. So, they shouldn’t waste their valuable practice time on distractions like, well, everything else. It’s simply not true. In a recent discussion with a graduate from the famed Yehudi Menuhin School, we touched upon the challenges even the most talented and cultivated young musicians face when having to enter the “real world”. Being picked up by a famous agency before you’re twenty might look like a hallmark of great success, but can actually turn out to be a harmful road to early burnout – being too much, too soon.

Balanced goal setting and planning

Many students asked about goal setting and identified this as a key challenge for them. It is easy to become disorientated as a young professional with all the things that you (think you) need to do and all the open possibilities that seem to be there, at least in theory, or in dreams. I suggested we try to approach goal setting as a way of placing one’s understanding of self, artistic dreams, life choices, and risk tolerance, into an understanding of the environment, the music ecosystem. And then ask: What can I do to get the life I want, given the way the professional music world really works? Goal setting basically becomes an exercise of reverse-engineering, constructing a dream result within the nuts-and-bolts real world.

A good mental exercise for this is to think of someone who already has it all and do research on how they got there and what is the team and infrastructure around their success. Who are they working with? How did they end up there (in the agency, management, label, opera company, etc.)? Could you also work with these people? Where do they go so that you might reach them (such as business networking events, etc.)? If you could meet them then what would you pitch? What would it take for you to have something to pitch? Whose help do you need, where to get it? Etc. It sounds easier said than done, but it can be instructive to try.

One aspect of goal setting that seems to confuse us is that it happens on such different levels, from having a life dream to planning your week. I provided the participants of the workshop with a framework for thinking about goal setting on three distinct levels and then checking the alignment with each level. These would be:

- Long-term trajectories – on this level it’s about the creative and artistic dreams and having an idea of what such a life feels like as a process. Planning and goals are too restrictive on such a scale, so I’d suggest to think rather in terms of trajectories, open ended directions with a desired state of being on the horizon, but no clear path yet visible. Until you’re really accomplished with contracts running years ahead, it doesn’t make much sense to plan anything beyond a few years in detail.

- Medium-term goals – or, what could be seen as strategic goals. On this level it’s about setting concrete, ambitious, clear goals that you can describe in some detail. This will allow you to reverse-engineer potential paths to achieve them.

- Short-term goals – or, weekly and monthly task management. It’s about delivering with quality the projects you already have on the note stand, while staying mentally and physically fit. It’s about being efficient and professional.

- Balancing between different levels of goals – It’s possible that within the daily hustle the biggest dreams fall out of sight and you might find yourself on a treadmill of delivering project after project with no time to gaze further ahead. It’s natural. That’s why we need to consciously plan for regular reflection and ask: what am I doing every day to make my dreams come true? Is the life I have created satisfactory? If not, what am I or should I be doing to change that?

The framework is visualised in figure 3.

Figure 3. Framework for balancing the three levels of goal setting

Part III. Learnings

I enjoyed doing the workshops very much, even if I was also worried about whether I actually have anything useful to contribute. After all, there’s nothing scientific about this at all, it all relies on my personal experience and basic deductive ability. I learned a lot. Here are a few key takeaways I noted for myself.

- I can talk, teach and offer various tools and frameworks for thinking, but in the end all that matters is if the participants can try them out for themselves and get some guidance in case they get stuck. Therefore, a one-off workshop, even if half a day long, is at best an introduction that needs a longer process to follow it.

- Interactive assignments in an online setting require a facilitator in each group. It’s not so much that the participants can’t get things done on their own, but in order for the assignment to really be useful they also need feedback. Coming back from the assignment, offering everyone a decent time slot to pitch, discuss and feedback takes the session to a full day easily. In the future, if there’s more than 2-3 groups of 4-5 people at the most, I will consider group work only if I have a full day or even several days for the sessions.

- Using online tools can be great, but time must be allocated to get everyone on board, troubleshoot the odd glitches that some might have and get everyone working. I used a Miro board for interactive work. I had prepared imaginary cases (see figure 5) on case boards with a process map the participants had to fill. It all seemed very logical in my head, but in reality it wasn’t as effective. From feedback I read that while it was fun to do, further efforts and time would’ve been necessary to really discuss the findings of each group, give more feedback and address the question of how they can make personal use of this work. This would again need much more time than I had planned.

- Real learning only happens when the participants can somehow relate what they hear to their own particular personal circumstances. This requires a longer process, personalised homework and one-to-one elements. This is much work for the facilitator/teacher to read through the participants homeworks, so what begins as a quick and practical workshop becomes a course. Actually, I’m not sure I have ever experienced quick and practical formats myself. “Practical” always needs time.

- The participants came from different countries and institutions. It was a surprise to me how different opportunities and support infrastructure is available depending on where you come from. Some had already had several types of career coaches, mentoring and practical courses, while some admitted that in all the long years of their academic training these issues were never really addressed. In some cases, these topics of how to prepare for a “real life” professional world of work seem to be handled in some perfunctory courses that, while ticking the boxes required for curriculum accreditation, offer only little real help for students.

In summary, there is much to be done in the academic sphere to help the young professionals we so carefully polish in terms of academic excellence to find their feet in the “academic hereafter”, which is actually life itself. If career the noun is indeed an outdated concept for a contemporary freelance artist, perhaps we should then try and help them get ready for career the verb.

Figure 5. Interactive assignment for a group of participants.